Effect of Antidepressant Switching vs Augmentation on Remission Among Patients With Major Depressive Disorder Unresponsive to Antidepressant Treatment: The VAST-D Randomized Clinical Trial

This randomized clinical trial investigated the relative effectiveness and safety of three common treatment approaches for major depressive disorder (MDD) in patients who did not adequately respond to their initial antidepressant treatment. The study aimed to assess the effects of three next-step treatment strategies, including switching to a norepinephrine/dopamine-reuptake inhibitor (NDRI), augmenting with an NDRI, or augmenting with an atypical antipsychotic.

According to the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study, approximately 33% and 49% of major depressive disorder (MDD) patients achieve remission and response, respectively, following their initial antidepressant therapy.1 As a result, a large proportion of patients may continue to experience residual symptoms. Residual depressive symptoms in patients with MDD can be associated with an increased risk of relapse, psychiatric hospitalizations, disability, and suicide.2 Additionally, research indicates that delays in finding an effective therapy can reduce the likelihood of achieving a response, highlighting the need for timely management and treatments.1 For patients who experience partial response, next-step treatment strategies can include optimizing the dose, switching antidepressants, or augmenting the initial antidepressant.3 Understanding the potential outcomes associated with each management approach can help healthcare providers make more informed treatment decisions with the ultimate goal of helping patients.

Study Rationale

The primary objective of the Veterans Affairs Augmentation and Switching Treatments for Improving Depression Outcomes (VAST-D) study was to determine the relative effectiveness and safety of three treatment strategies commonly used for patients who did not respond adequately to at least one antidepressant treatment trial of adequate dose and duration.4 While the earlier STAR*D study examined the effect of some switch or augmentation strategies used for patients with MDD, it did not include second-generation antipsychotics or atypical antipsychotics, which are currently used as adjunctive treatment in some adult patients with MDD who experience an inadequate response to their antidepressant.1 The VAST-D study sought to assess the effects of three next-step treatment strategies, including adjunctive use of atypical antipsychotics.

Study Design and Methodology

The VAST-D study was a multi-site, randomized, single-blind, parallel-assignment trial. It enrolled 1,522 adults (ages 18 to 75) diagnosed with MDD without psychosis who experienced inadequate response to at least one antidepressant treatment trial of adequate dose and duration. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three treatment groups4:

- Switch to a different antidepressant, a norepinephrine/dopamine-reuptake inhibitor (NDRI) (n=511)

- Augment current antidepressant with an NDRI (n=506)

- Augment current antidepressant with an atypical antipsychotic (n=505)

The acute treatment phase lasted 12 weeks, followed by a continuation phase for up to 36 weeks. The primary endpoint assessed was remission of MDD symptoms during the acute treatment phase as measured by the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician-Rated (QIDS-C16), and remission was defined as a QIDS-C16 score of five or less for two consecutive weeks during the acute treatment phase. The secondary endpoints of the study included response, relapse, and adverse effects. Response was defined as a 50% reduction in QIDS-C16 score or improvement on the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I) scale to a score of two or one at any scheduled visit through week 12, and relapse was defined as a QIDS-C16 score of 11 or more during the continuation phase after achieving remission in the acute treatment phase.4

Study Findings

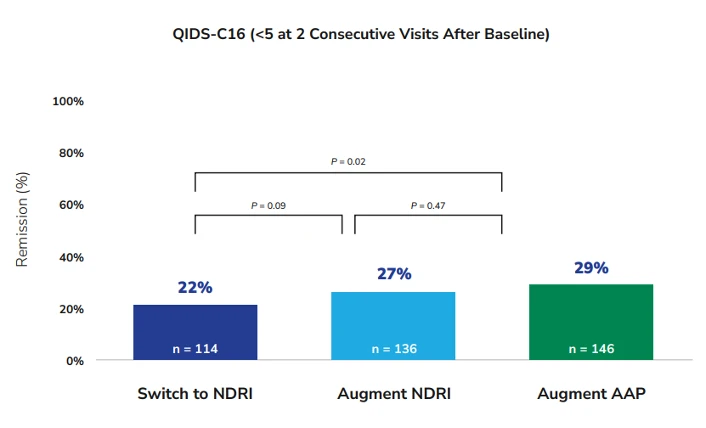

The primary outcome of the study, remission rates at 12 weeks, was statistically significantly higher in the augment-atypical antipsychotic group (28.9%) compared to the switch-to-NDRI group (22.3%, relative risk [RR], 1.30) but not compared to the augment-NDRI group (26.9%). The rate of remission in the augment-NDRI group was not significantly different from that of the switch-to-NDRI group. Time to remission was not significantly different between any of the groups.4

Figure 1. Remission rates among patients in the three treatment groups as measured by the QIDS-C16. Adapted from Mohamed S, Johnson GR, Chen P, et al. JAMA. 2017;318(2):132-145.

AAP = atypical antipsychotic, NDRI = norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, QIDS-C16 = 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating

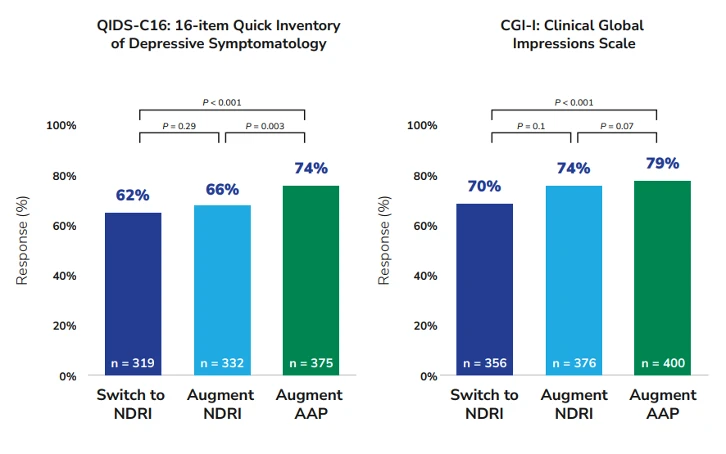

The secondary outcome of response measured by QIDS-C16 at 12 weeks was significantly higher in the augment-atypical antipsychotic group (74.3%) than in either the switch-to-NDRI group (62.4%, RR, 1.19) or the augment-NDRI group (65.6%, RR, 1.13). The Cox analysis of response based on the QIDS-C16 score showed that the cumulative response for the augment-atypical antipsychotic group was greater than that of both the switch-to-NDRI group (hazard ratio [HR], 1.32) and augment-NDRI group (HR, 1.23). However, there was no significant difference in the cumulative response between the augment-NDRI group and switch-to-NDRI group (HR, 1.05). Similarly, the response measured by the CGI-I was significantly higher in the augment-atypical antipsychotic group (79%) compared to both the switch-to-NDRI group (70%, RR, 1.14) and the augment-NDRI group (74%, RR, 1.07).4

Multiple-imputation sensitivity analysis for protocol remission at week 12 showed comparison of the augment-atypical antipsychotic group vs the switch-to-NDRI group to be statistically significant (RR, 1.33), but not the augment-NDRI group vs the switch-to-NDRI group (RR, 1.16). For responses defined by the protocol, there was a statistically significant effect for the augment-atypical antipsychotic group vs the switch-to-NDRI group (RR, 1.26) but not for the augment-NDRI group vs the switch-to-NDRI group (RR, 1.10). Among patients achieving remission at 12 weeks, there were no significant differences in the secondary outcome of relapse among the three treatment groups.4

Figure 2. Response rates among patients in the three treatment groups as measured by the QIDS-C16 and the CGI-I. Adapted from Mohamed S, Johnson GR, Chen P, et al. JAMA. 2017;318(2):132-145.

AAP = atypical antipsychotic, NDRI = norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor.

Adverse Events (AEs)

Serious AEs

AEs were reported in 165 patients (10.8%). Of those, a total of 207 were serious AEs. There were 8 deaths among study patients during the safety reporting period. Investigators and the data and safety monitoring committee agreed that the deaths were not study medication-related.4

Nonserious AEs

The study reported 4,356 nonserious AEs, which occurred more frequently in the switch-to-NDRI group than in other groups. Nonserious AEs associated with the switch-to-NDRI group included nausea, irritability, and hypomania. Nonserious AEs occurring more frequently in both the switch-to-NDRI and augment-NDRI groups than in the augment-atypical antipsychotic group included anxiety, decreased appetite, dry mouth, and increased blood pressure. Nonserious AEs occurring at a higher rate in the augment-atypical antipsychotic group than the other two groups included fatigue, increased appetite, increased weight, akathisia, somnolence, and abnormal values for several laboratory tests.4

At week 12, weight gain of 7% or greater was more frequent in the augment-atypical antipsychotic group (9.5%) than in the switch-to-NDRI group (2.3%) and the augment-NDRI group (1.9%). For patients who continued to week 36, the rate of weight gain of 7% or greater was similarly higher in the augment-atypical antipsychotic group (25.2%) compared with the augment-NDRI group (5.2%) and the switch-to-NDRI group (5.2%).4

Additional VAST-D Studies Analyses

Forty-seven percent of participants in the VAST-D study had concurrent posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).5 To assess whether the presence of concurrent PTSD affected the level of treatment effects seen with the three next-step treatment options, the authors of the original study conducted a secondary analysis. They found that the rates of remission and response within 12 weeks were 43% and 25% lower in patients with PTSD as compared with those without, respectively. The treatment effects on remission, response, and relapse seen with each treatment option in patients with or without concurrent PTSD, however, were not significantly different.6

Study Limitations

Limitations of the study include:

- Only one antidepressant and one antipsychotic were evaluated, making the generalizability of the results uncertain.4

- Only 74.7% of the patients completed the 12-week acute treatment phase, and the differences in outcomes between groups were small in magnitude.4

- The study only included Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patients, who are predominantly male and White, with moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms.5

- In addition to the large proportion of patients with PTSD, about 37% of participants reported suicidal ideation within the last three months; 13% met criteria for current alcohol abuse or dependence. Therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to a wider population.5

- Many patients who were diagnosed with nonpsychotic MDD and failed initial pharmacotherapy still did not meet the inclusion criteria because they had already failed a trial of a medication used in the VAST-D trial or that was otherwise contraindicated, making extrapolating results to the general population challenging.5

- The study used scales that are not used in clinical practice, including an adapted version of the Brief Grief Questionnaire, the Mixed Features Scale, and the Positive Mental Health Questionnaire, the latter two of which had not been validated or field-tested.5

- The study used the age of onset of first diagnosis of MDD instead of the age of onset of first major depressive episode or other key symptoms, which are potential prognostic indicators.5

- Information was not collected on MDD “subtypes” (eg, atypical, anxious) or if onset was early, late, or seasonal.5

Clinical Relevance of Findings

More than half of patients with MDD do not achieve remission after their first course of antidepressant monotherapy.1,3 Those who do not reach remission often face poor clinical outcomes. This underscores the importance of identifying and implementing effective treatment approaches that can help lead to a response earlier in the patient’s journey. The VAST-D study provides valuable insights into the effects of “next-step” treatment strategies that are commonly used for patients who do not respond adequately to their initial antidepressant therapy.

VAST-D is noteworthy for examining the effects of augmenting with an atypical antipsychotic, among other treatment strategies. In this study, augmentation with an atypical antipsychotic was shown to result in remission in some patients with MDD who did not have an adequate response to first-line antidepressant monotherapy. Also, it’s important for clinicians offering augmentation with an atypical antipsychotic to obtain baseline screenings, educate patients on the need for follow-up, as well as monitor for potential adverse events, such as weight gain, akathisia, and metabolic changes, that can be associated with atypical antipsychotic use.4

Future Research Directions

Given the limitations cited above, it will be important to conduct similar trials among larger and more diverse populations of patients with MDD in the future. Including a broader range of medications within the drug class for comparison and evaluating their long-term effects may help enhance our understanding of the current treatment approaches available for MDD.

Provider's Insights on the Potential Clinical Implications of the Study

1) How do you interpret these findings in the context of current treatment strategies utilized for patients with MDD?

“The VAST-D trial offered important insights into the effectiveness of different second-step treatments for patients who do not respond to initial antidepressant therapy. The primary outcome was that augmenting with an atypical antipsychotic resulted in significantly higher remission rates compared to the switch-to-NDRI group but not compared to the augment-with-NDRI group. The secondary outcome was that augmenting with an atypical antipsychotic had higher response rates than either the switch-to-NDRI group or the augment-with-NDRI group.”

2) Is there a guideline consensus on the second-step treatment strategies for patients who do not respond and experience residual symptoms after their initial antidepressant therapy?

“There is a consensus that the recommended second-step treatments for patients who do not achieve a response to their initial antidepressant can include switching, augmentation, or combination therapies. However, there are differences in the timing and specificity of recommendations for implementing augmentation vs switching.7 For patients experiencing nonresponse (<25% decrease from baseline on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score),8 the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder recommends changing to a different non-monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressant, for example, from one SSRI to another SSRI, from SSRI to SNRI, or from SSRI to a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA). Augmentation or combination therapy is recommended for patients with a partial response, defined as those with <50% but ≥25% decrease from baseline.8,9 The APA does not specify which strategy of the augmentation or combination therapies should be implemented first. While providing similar recommendations, the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2023 Update on Clinical Guidelines for Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults does provide additional detail about the recommendations for second-line therapy. CANMAT recommends considering augmenting earlier in the treatment process if patients do not respond fully to the first or second antidepressant therapy.9,10

The VAST-D findings suggest that augmentation with an atypical antipsychotic can be an effective second-step option for MDD patients who do not adequately respond to antidepressant therapy. In general, providers should consider many factors, such as patient characteristics, symptom severity, prior treatment history, comorbidities, and side effect concerns, when making treatment decisions.”10

Michael Banov, MD

Michael Banov, MD, is the medical director for Psych Atlanta and a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the Medical College of Georgia. He is triple board-certified in adult, adolescent, and addiction psychiatry. He has been the principal investigator for numerous clinical trials related to psychiatric disorders, investigating new and existing compounds in the management of both acute and chronic psychiatric conditions.

References

Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905-1917. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905

- Tranter R, O'Donovan C, Chandarana P, Kennedy S. Prevalence and outcome of partial remission in depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2002;27(4):241-247.

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28

- Mohamed S, Johnson GR, Chen P, et al. Effect of antidepressant switching vs augmentation on remission among patients with major depressive disorder unresponsive to antidepressant treatment: the VAST-D randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(2):132-145. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.8036

- Zisook S, Tal I, Weingart K, et al. Characteristics of U.S. Veteran patients with major depressive disorder who require "next-step" treatments: a VAST-D report. J Affect Disord. 2016;206:232-240. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.07.023

- Mohamed S, Johnson GR, Sevilimedu V, et al. Impact of concurrent posttraumatic stress disorder on outcomes of antipsychotic augmentation for major depressive disorder with a prior failed treatment: VAST-D randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(4):19m13038. doi:10.4088/JCP.19m13038

- Jain R, Higa S, Keyloun K, et al. Treatment patterns during major depressive episodes among patients with major depressive disorder: a retrospective database analysis. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2022;9(3):477-486. doi:10.1007/s40801-022-00316-4

- Nierenberg AA, DeCecco LM. Definitions of antidepressant treatment response, remission, nonresponse, partial response, and other relevant outcomes: a focus on treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 16):5-9.

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

- Lam RW, Kennedy SH, Adams C, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2023 update on clinical guidelines for management of major depressive disorder in adults. Can J Psychiatry. 2024;69(9):641-687. doi:10.1177/07067437241245384

This summary was prepared independently of the study’s authors.

This resource is intended for educational purposes only and is intended for US healthcare professionals. Healthcare professionals should use independent medical judgment. All decisions regarding patient care must be handled by a healthcare professional and be made based on the unique needs of each patient.

Reach out to your family or friends for help if you have thoughts of harming yourself or others, or call the National Suicide Prevention Helpline for information at 800-273-8255.

ABBV-US-02108-MC, V1.0

Approved 08/2025

AbbVie Medical Affairs